As war broke out across Europe in August 1914, Britain had very few military airships. While Germany had invested time, money and faith in airship development, Britain had a handful of non-rigid and semi-rigid experimental (and foreign) airships with just 195 airship personnel. Germany on the other hand had ten tried-and-tested airships operated by both the German Navy and Army.

But Germany’s advantage lay in more than the fact that she had more airships. She was, “airship-conscious”1.

Germany had been training men in airship activities since the early years of the century; her commercial fleets had provided first-class training for pilots; and she had the capability, facilities and know-how to construct airships quickly and efficiently (within a year Germany’s airship fleet had swelled to twenty-nine).

Before the war, from 1 January 1914 all British Army and civilian airships had been operated by the Royal Navy and military personnel that did not trust aeroplanes, such as the brilliant Edward M. Maitland, were allowed to transfer across to the Airship Service. On 1 July this division officially became the Royal Naval Air Service and was now fully under the control of the Admiralty. However, not everyone in the Admiralty could see the benefit of airships to traditional sea-base warfare. As an early report stated…

“… the policy of the Government with regard to all branches of aerial navigation is based on a desire to keep in touch with the movement rather than hasten its development. It is felt that we stand to gain nothing by forcing a means of warfare which tends to reduce the value of our insular position and the protection of our sea power.”2

This attitude was very much based on the experience of previous wars and didn’t take into account the two new weapons of warfare – the aeroplane and the submarine. Because of an unwillingness and sluggishness to embrace these two technologies Britain was left in an uncomfortable position at the start of the war. Very soon into hostilities the British Fleet, probably the most powerful ever, was effectively driven out by a few German submarines to find safer hiding places far from the North Sea. This opened up the whole of the East coast of England to hostile attack by air and sea.

The airship was, without doubt one of the most effective counter-measures against the submarine. As J. A. Sinclair explains in his book Airships in Peace & War…

“Its hovering powers, its ability to remain in the air for days at a time, its independence of engine-power in an emergency – all these things combine to make an airship singularly suitable for reconnaissance, particularly over the sea, and it is in that sphere that the airship excels.”

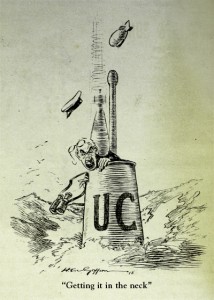

Indeed, British airships were to prove a formidable deterrent to the U-boat while performing reconnaissance, patrolling, mine-hunting and convoy escort duties. They were responsible for driving the U-boats underwater and out of harm’s way where, previously, they had been free to attack every kind of ship from the smallest trawler to the largest battleship. As an illustration of the value or the airship as a deterrent it is alleged that the log of one captured German submarine was found to contain the following entry: “Sighted airship – submerged.”3 Even submerged to a considerable depth, in some waters, U-boats could still be seen by sharp-eyed airshipmen and they learned to look out for other tell-tale signs such as oil trails and gulls flying in the wake of a periscope. As far as can be known (except for one single occasion) no ship was sunk by a U-boat while guarded by an airship.

Indeed, British airships were to prove a formidable deterrent to the U-boat while performing reconnaissance, patrolling, mine-hunting and convoy escort duties. They were responsible for driving the U-boats underwater and out of harm’s way where, previously, they had been free to attack every kind of ship from the smallest trawler to the largest battleship. As an illustration of the value or the airship as a deterrent it is alleged that the log of one captured German submarine was found to contain the following entry: “Sighted airship – submerged.”3 Even submerged to a considerable depth, in some waters, U-boats could still be seen by sharp-eyed airshipmen and they learned to look out for other tell-tale signs such as oil trails and gulls flying in the wake of a periscope. As far as can be known (except for one single occasion) no ship was sunk by a U-boat while guarded by an airship.

Over the four years of conflict from the outbreak of war to the Armistice, another 225 airships were delivered which, in all, put in 88,000 hours of flying, amounting to more than two million miles travelled. During the time of hostilities only 48 officers and men of the airship service were lost due to enemy action and accidents.

British airships certainly successfully attacked and sank German submarines, both alone and with the help of surface ships, but it is as a deterrent that airships helped tip the balance in favour of Britain in the war at sea. Without them the allies would have undoubtedly lost many more ships which might have given Germany the chance to starve Britain into defeat. As Patrick Abbott in his book The British Airship at War sums-up, “The British airships did not win the war by themselves, but without them the war might never have been won.”

- Airships in Peace & War, J. A. Sinclair, 1934

- Ibid

- The British Airship at War, Patrick Abbott, 1989

NS11 – As Bright As Day is very much a work in progress and has been made possible by the generous and enthusiastic support of many individuals and organisations. If you have any information, records or material relating to British NS Class airships we would be very interested to hear from you – especially anyone related to members of the crew of NS11 or any airship of the class during their service with the RNAS or RAF during and beyond WWI.

NS11 – As Bright As Day is very much a work in progress and has been made possible by the generous and enthusiastic support of many individuals and organisations. If you have any information, records or material relating to British NS Class airships we would be very interested to hear from you – especially anyone related to members of the crew of NS11 or any airship of the class during their service with the RNAS or RAF during and beyond WWI.

Latest