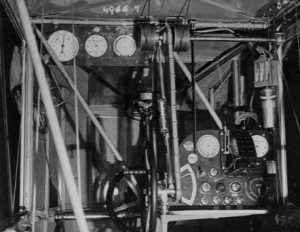

The North Sea class airship N.S. 11 was assembled and tested at RNAS Kingsnorth on the Isle of Grain, Kent. During July 1918 her two 260hp FIAT engines were prepared for fitting and propellors balanced. In early August she was fitted with a “East Fortune” type car built by Frederick Sage & Co. Ltd. N.S. 11 had a separate power car unlike the Wheelwright-design airships.

On 22 August she took her first trial flight. Although ready for delivery, owing to a fire at Howden and shortage of shed space, she was held at Kingsnorth, until on 6 September Captain W. K. Warneford accompanied by 2nd Officer Captain Parry flew her to Longside via Howden. On 14 September Warneford and Parry took her on her first recorded Northern Patrol of 11 hours, 11 minutes duration.

So began the story of Warneford and NS11 – a partnership that would bring glory and, ultimately, disaster less than a year later.

With patrols, convoy escort duties and submarine hunts through September and October 1918, Warneford and NS11 racked up many hours of flying time from Longside. The day after Armistice NS11, in company with NS12 undertook an extended Eastern Patrol as far as the Norwegian coast to Skudenes and the island of Utsira – reportedly the first crossing of the North Sea by an aircraft.

On 17-19 November NS11 undertook a record 61 hour, 21 min Central and Southern patrol in mist, fog and rain. One notable event took place while escorting HZ convoy in company with NS11. Warneford requested drinking water from the Melpomene, brought the airship down to about 20 feet above her masts and dropped a line to pick up two one gallon bottles of water. Warneford obviously thought this involved considerable risk to the airship so did not think it advisable to pick up any more. By the morning of 19 November all the food was finished and the crew were down to emergency rations and drinking the water ballast – having been on half-rations for the previous 24 hours. The crew must have been hungry as they risked coming low over a trawler and picked up fish in a canvas bag. These would have no doubt been cooked on the ‘hob’ mounted on one of the engine exhausts.

This trip constituted an endurance record for a British non-rigid airship and severely tested the crew as well as the airship. The only mechanical issues were that the dynamos would not charge under an air speed of 30 knots that, in consequence, meant that lights in the car could not be used for more than a few seconds at a time.

The official log for this trip can be found here.

For the remainder of November 1918 NS11 was used for navigation instructional flights and was not flown during December and January being “temporarily out of commission” from 16 December. In preparation for decommissioning the airship was prepared for deflation on 27 January 1919, but the order was rescinded and NS11 was made serviceable again on 31 January.

At 1400 on 9 February, under the command of Warneford, NS11 took off on what was to be a world record flight for any kind of aircraft of 101 hours, 50 minutes. The 1,400 mile (2,300 miles through the air) patrol took them as far north as Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands (where they photographed the German fleet) and south to Farne Island off of Northumberland. The chart and log of this patrol can be seen here.

Following the flight, Warneford reported:-

“Throughout the flight no trouble of any kind whatsoever was experienced, except one slight defect in the engines, and on coming down, the rudder and elevator controls were examined and not a trace of wear was found anywhere, despite the fact that one rudder control had been in for about 150 hour flying previous this, including the flight of 61 hours.

It is considered that it would be impossible to get a ship to be more reliable, as from the time she was commissioned (September 1918) to the present date there have been no replacements of an kind except elevator and rudder controls.

The engines gave no trouble at all, except the magneto drive stripped on the starboard engine. New parts were picked up from East Fortune and replaced the port engine has now run 350 hours and given no trouble of any kind.”

Warneford noted that it was necessary to have a considerable quantity of water on board for emergencies – drinking water was used to replenish the engine radiators. In fact, by the end of the flight only one radiator had sufficient water so only one engine could be run.

Warneford also pointed out the effects of superheating:

“Another point which was very forcibly brought home, was the fact that whilst cruising so slowly, it is necessary to keep the ship more or less in trim and equilibrium, and any large differences in temperature are very soon felt.

For instance – when flying in the sun over the sea at 20 knots, the ship heated up so much that she could not be kept down. About an hour afterwards the sun was obscured by a bank of clouds and the ship rapidly became almost uncontrollably heavy, and the engine revolutions had to be increased to keep her up. It was necessary to drop nearly 100 gallons of petrol before landing. This amounted to a loss of lift of nearly 700 lbs in a space of about 2 hours. Applied to a rigid of 2 million feet capacity, this would represent a loss of lift of over 3,500 lbs.

All this points to the absolute necessity (if long flights are to be carried out) of introducing some scheme of water recovery, which will both allow the ship to be kept in equilibrium without valving gas; also enable one to have a large reserve supply of ballast in case of emergency.”

Of the crew Warneford reports:

“The crew were in no way fatigued, except the 1st Engineer [Sergt. Mech J. Wrenn] who had to perform a great deal of heavy work, such as starting the engines, etc. When he had started up one engine single-handed, he was so fatigued that he collapsed and fell off the rail, but fortunately, he was caught by a piece of 5 cwt wire between the rolling guys and recovered himself.”

What is clear from this report is that Warneford was a skilled engineer and airshipman who cared for his crew. He also recommended that Remy-ignition should be used for starting up the engine single-handed, “in order to allow the engineer off watch to have undisturbed rest, which in a ship of this size, is absolutely necessary.”

A total of 50 hours, 45 minutes was flown during March 1919. This included a widely-reported 40 hours, 30 minutes circuit of the North Sea from the 16-18 March. This 1,285 air-mile voyage, which took the form of a circuit embracing the coast of Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein, Heligoland, North Germany, and Holland, was characterised by extremely unfavourable weather conditions. Starting from an airship station on the Firth of Forth at 3.45 p.m. on March 16, the airship laid a straight course for Denmark, the Dogger Bank Noord Lighthouse being passed at 1 a.m. The Lemvig Light Vessel, 370 miles from the base, was picked up at 5 a.m., and turning south, the airship cruised down the coasts of Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein towards Heligoland, which was reached at 8 a.m. Passing at a distance of four miles from the island, a new course was set for the Frisian Islands, and at six o’clock in the evening the airship was off Terschelling, the wind having now attained a speed of 30 knots from the north-west. After leaving the Dutch coast the wind grew stronger, and one engine broke down. According to the New York Times of 23 March 1919, “during the last stage of the voyage the wind was very violent and the crew had the greatest difficult in controlling the ship. All suffered intensely form seasickness, especially the pilots and coxwains.”

It was decided to hold on, and a “landfall” was made at the North Foreland. By this time petrol was running short owing to the necessity of running at full power earlier in the voyage, and one engine only was running – this on five cylinders out of six. At 8.15 a.m. on 18 March a landing was successfully effected at an aeroplane station close by.

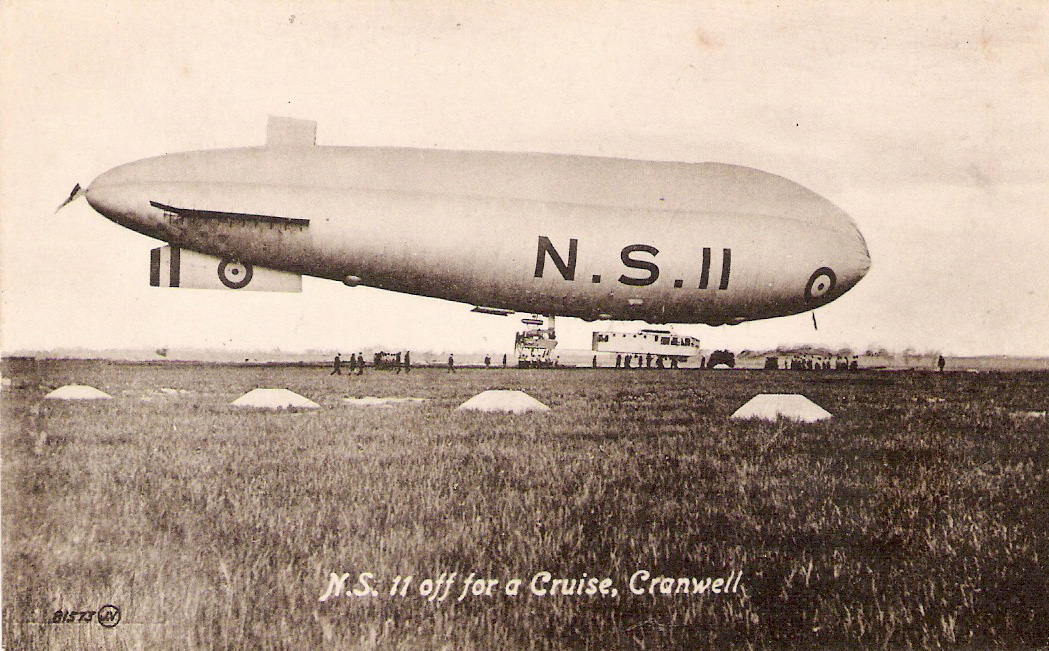

The airship was transferred to Kingsnorth and then on 31 March flew to Cranwell via Pulham and Howden.

At this point one gets a sense of the airship service being wound down. NS11 flew just 7 hours, 45 minutes during April and 48 hours, 15 minutes in May while at Cranwell. In June she was transferred to Pulham and in early July she is known to have cruised over London (see London from an Airship).

In the early hours of 15 July 1919, on a flight over the North Sea, NS11 exploded and was lost with all hands off the coast of Norfolk.

NS11 – As Bright As Day is very much a work in progress and has been made possible by the generous and enthusiastic support of many individuals and organisations. If you have any information, records or material relating to British NS Class airships we would be very interested to hear from you – especially anyone related to members of the crew of NS11 or any airship of the class during their service with the RNAS or RAF during and beyond WWI.

NS11 – As Bright As Day is very much a work in progress and has been made possible by the generous and enthusiastic support of many individuals and organisations. If you have any information, records or material relating to British NS Class airships we would be very interested to hear from you – especially anyone related to members of the crew of NS11 or any airship of the class during their service with the RNAS or RAF during and beyond WWI.

Latest